Photo by Jason Goodman on Unsplash

It is much harder to listen effectively than most of us realise, and we tend to think we listen well when perhaps we don’t. Effective listening is so important not only for personal relationships (who wants a friend who never listens) but also for building trust in healthy organisations.

For example, leaders encourage people to “speak up” yet often express frustration about the silence that follows requests for ideas or challenges. But maybe the challenge lies in how leaders listen rather than in some deficit on the part of employees.

The importance of Psychological Safety

When researching how organisations listen to their employees “psychological safety” often emerges as a core theme. 1 Psychological safety is the belief that you won’t be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes. 2

Encouraging a culture in which people feel free to speak up is important for at least three reasons:

- Motivation: listening creates a sense of belonging by confirming that everyone’s view is welcome

- Risk Management: listening increases the ability to identify and spot problems that people will feel free to raise; and reduces the risks of future mistakes being made, harm being done and reputations damaged

- Change management: listening increases the likelihood that teams and organisations can change and innovate by welcoming ideas that challenge how things get done.

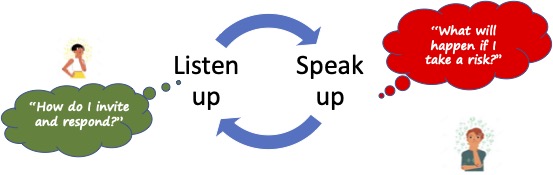

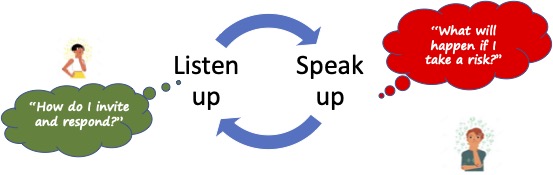

There is a circularity between speaking up and listening up – see the diagram below. Team leaders need to take the initiative to encourage people to speak up by creating safe team spaces at a micro level. At the macro or organisational level, the leader needs to create a listening strategy and culture that encourages and celebrates employee voice.

I’ve spent years listening to leaders, managers, employees and special interest groups (e.g., high potential managers, union representatives) talking about communication at work. Recently I’ve run international surveys and focus groups with Dr Kevin Ruck (PR Academy founder) and Howard Krais (Communication Director, Johnson Matthey) in which we have focused on how organisations listen. I’ve also spent time recently talking to some respected colleagues who work in management and leadership to explore what they see as the barriers to listening up (see acknowledgements below).

I’ve captured below the things that stand out, and some of the things that organisations can do to make it easier for people to listen effectively.

What makes listening up hard?

- Closed minds

The biggest barrier to listening, and by implication to insight and new ideas, is the simple fact that people often enter a conversation with their minds made up. If people have fixed views, the narrative in their heads constantly filters whatever they hear. In our second and fourth “Who’s Listening” reports we looked at best listening practice at an organisational and individual level, and “Open Mindsets” emerged as a critical enabler in both.3

During times of change at work listening is particularly critical. However, leaders and managers are the champions of whatever change is needed. This makes it even more likely that they will be preparing a response or a “solution” to any pushback or objections, making it harder for them to listen and making others feel that speaking up will make no difference to the course of action under discussion.

- Bias

People are biased – their brains are designed to create shortcuts to aid decision making and for protection. For example, people form “in-groups” with those who share common goals and are more disposed to listen to those they think are like them. The familiar problem of organisation silos – in which information flows poorly across organisational boundaries – often has an in-group mentality as a contributory cause. The ability to listen is affected by, often unconscious, bias. Tell-tale phrases that bias is limiting listening include “They would say that” or “I know what they will say”. As a result, people from other departments, levels or countries find it more difficult to be heard and are likely to speak up less. Or, voices may become more strident and the conversation becomes adversarial rather than constructive.

On the flip side, bringing in external agents with perceived expertise can improve their impact, even if their recommendations are no different from internal agents.

- Power

One particular form of bias that is highly relevant to the challenge of listening up is concerned with power. Power affects relationships and interferes with the capacity to listen. People who have power over others find it easier to be heard. This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. Our brains have evolved to take heed of more powerful members of the tribe. But for a leader it works in reverse increasing the difficulty of really listening to those over whom the leader has power. 4

There may be various explanations for this. For example, do leaders believe they need to be hard-nosed because they have to take difficult and unpopular decisions and empathetic listening may make it harder to make these decisions? They also face competition for their time amongst those over whom they have power, and rationing listening is a necessary coping strategy.

- Risk

Listening up is taking some risk as an individual (in the same way that speaking up involves risk). These risks essentially involve perceived challenges to one’s credibility, status or position and involve fears about exposing oneself to ridicule. For example, what if:

- I do not know the answer to a question?

- I say something in response that is contradicted by others or more senior colleagues?

- I’m presented with a need that cannot be met?

- I unearth mixed and irreconcilable perspectives, and open a Pandora’s Box of insoluble dilemmas?

- I make myself look weak and out of control to others in more senior positions?

These concerns may identify some narrow and false perspectives about what it means to be a good leader. But what matters is that they drive how people behave. Not speaking up is normally based on an assumption that an individual risks exposing him or herself to ridicule or censure if they do speak up. Likewise, not listening up can also be based on assumptions about how I will appear to others.

- Lack of self-awareness

The fifth barrier is poor self-awareness involving the perception that people listen well when they do not. Research in the NHS and elsewhere identifies the self-enhancement bias in which we rate our own competence at listening higher than others. 5 In other words, we think we listen well but we do not. This “blind spot” means that those who most need help to improve the way they listen are least aware of the need. Some of the issues here can include:

- The lack of appreciation that power has a major impact on those without it. Leaders need to work to make others feel safe to speak their mind (“My door is always open” just reminds people that there is a door)

- As mentioned above, those with power discount the perceptions of those over whom they have power

- Failure to appreciate the reasons why it makes more sense for people not to speak up. 6 Given this, leaders and managers need to guard their responses and reactions carefully when they are listening and work hard to help people to speak up.

What can make listening up easier?

In order for people to speak up, managers and leaders need to listen up well. To do so they need to:

- Frame the need for listening

- Set the right role models

- Use listening tactics

- Adopt a listening mindset and behaviours

- Act upon what they have heard and communicate what has been done.

Leadership needs to take responsibility for creating the environment in which the following can take place.

Frame the need for listening

- One of the key roles of the leadership team is to frame the overall need for listening, and the conversations that establish this require some careful thinking through of when and why listening is important. The goal is to position listening as critical to the organisation’s success, explaining why speaking up is important and how it links to the organisations’ purpose. This will vary by industry. For example: in healthcare effective listening and speaking up may increase patient safety; in manufacturing it may support innovation; in service businesses it may increase customer insight.7

- Helping the leadership team to recognise the need for this framing may involve using internal or external data to highlight the issue, and reflection within the team around individual biases and assumptions. Scenarios and case studies can be helpful tools, while getting the team to explore listening with each other can highlight some valuable lessons for the team and individuals

- Be clear about what and when listening is important. For example: listen for ideas and input to change management but not to strategy (once decisions have been made). Listen when the input is needed and avoid ‘false democracy.’ Along with this, ensure that leaders and managers take ownership of decisions that have been made which means that they need to understand them and their rationale.

Set the right role models

- The example set by managers and leaders signals what behaviour is valued. The most important requirements for listening well include:

- Responding appropriately to ideas, which may include rejecting them. The need is always to respect the contribution and the person providing the input; be it challenge, idea or disclosure. If the idea is just dismissed or the person is criticised or ridiculed others will not provide input.

- Speaking up by challenging and debating to encourage others, and asking others for input

- Showing vulnerability by relating events and stories in which the manager or leader themselves made mistakes, and emphasising lessons learned.

- To develop the ability to respond well, work with the leadership on challenges and objections that they fear meeting with their teams and employees. Working on these key implementation of strategy questions can help develop much more sensitive and empathetic responses that helps sustain the strategy while involving employees in discussions around the issues that concern them.

Use listening tactics

- Ask open questions that cannot be answered with yes/no responses

- Develop familiarity with structured sessions that encourage people to speak up. This could include using methodology and techniques from Appreciative Inquiry 8 and the Technology of Participation 9

- Other approaches to engage people in better conversations about the business and strategy include Open Space, Future Search, World Café and Big Conversation, Engagement Café and Knowledge Café

- Break people into small groups or pairs to discuss reflections on what they have heard and questions they might like to ask before inviting them to post or raise questions in open forums

- Prepare for questions in advance of meetings to help think through responses and as a leader or manager reduce the potential threat posed by questions that people will ask

- Listen in pairs to support each other and check that all the subtleties behind questions are picked up. Listening in pairs is especially helpful when listening to large groups

- Build internal networks so that managers and leaders can share stories and examples of the sorts of issues and questions people in the business want to discuss

Adopt a listening mindset and behaviours

- The art of listening involves not just hearing what others are saying but empathising with others’ feelings and seeking to understand others intentions. It’s not possible to listen well without building relationships – the two go hand in hand

- Create listening spaces and listen all the time. Listening is an “always on” function of leadership and management. While listening during meetings and the everyday act of running the business, set up spaces dedicated to giving people the opportunity to talk about what is on their minds

- Recognise that people do not always want answers to all the questions. They want to feel that they are being listened to and that their questions or suggestions are valued. Sometimes the question is more of a test to evaluate the ability of the manager or leader to handle the difficult question.

- Ask for feedback on how people experience listening to increase self-awareness and to encourage discussion about the art of listening.

Act upon what they have heard and communicate what has been done

- During the research we conducted into listening a consistent concern was the perception that when people put forward their views, they hear no follow-up nor learn of any actions or decisions that have been made based upon their input. The perceived lack of response is a major barrier to speaking up because people feel it is pointless. Yet at the same time I know many leadership teams that express astonishment at the idea that the findings from listening activities are ignored. Leaders often point to initiatives and decisions that stem directly from employee input. The trouble is that the connection between feedback and action gets missed. It is critical for leaders to ensure that they make the connection between what has been heard and what has been done, even if – as is usually the case – that action is based upon further discussion and deliberation prompted by the feedback, rather than a simple “you said, we did” type response.

Listening up is not about feeling comfortable

When talking about creating safety for those listening one of my colleagues made the astute point that the leadership role when listening is not about feeling comfortable. Getting pushback and objections from a group illustrates successful listening because the leader has encouraged speaking up. The leader benefits too because the input of different perspectives and alternative ideas enriches the quality of decision-making and the feeling of trust within groups.

So, when leaders get pushback and objections, the leader needs to congratulate the group for its courage and remember that the response that the leader gives to the next question or challenge is the test of his or her listening. Effective listening up involves recognising that what matters is always the response to the next question.

Notes

- Who’s Listening Research Report 1 2020; Couravel; PR Academy. Speak Up; Megan Reitz and John Higgins; FT Publishing 2019

- Source: What Is Psychological Safety at Work; Centre for Creative Leadership

- Who’s Listening Update 2 (2021) and Update 3 (2022); Couravel; PR Academy.

- Power and Perspectives not Taken; Galinsky, Psychological Science, 2006

- Speaking Truth to Power: Why Leaders Cannot Hear What They Need to Hear; Megan Reitz and John Higgins, British Medical Journal, Oct 2020

- The Fearless Organisation; Amy Edmondson, Wiley 2019

- A thorough exploration of the importance of framing is provided by Amy Edmondson: The Fearless Organisation; Wiley 2019

- See for example Appreciative Inquiry for Change Management; Lewis, Passmore and Cantore; Kogan page 2008

- The Institute of Cultural Affairs provides a starting point for Technology of Participation stories, tools and training: https://ica-uk.org.uk/about-ica/

Acknowledgements

A number of people helped by agreeing to talk to me about their experiences of listening up and I am extremely grateful for their input and support. I take full responsibility for the content but I would like to acknowledge those who helped and the particular insights they provided:

- Sheila Hirst, Authentic Leadership and Storytelling Coach who provided particular insights around the importance of self-awareness and openness as a key requirement for effective listening

- John Holmes, Chief Examiner, ABRSM whose listening credentials extend to the professional leadership of a disparate and specialist group of musicians and teachers

- Martin Horton, Leadership and Team Coach who differentiated feeling comfortable from feeling safe, and made the point that the leaders listening role involves generating challenge and support

- Jane Mitchell, IABC Fellow and LDA Design Trust Chair who highlighted the importance of the leader displaying vulnerability and framing the importance of listening, and who helped bring out the importance of a visible response as a key enabler of speaking up

- Simon Monger, President IABC UK&I, and Internal Communications, Change + Engagement Consultant at Simon Monger Ltd. Simon signalled the risks involved in listening up, and during online conversations identified the challenge that people often overate their listening abilities

- Andrew Morrison, Director of Corporate Affairs and Communications who told me some helpful stories about the importance of anticipating questions and listening in pairs, and the need for courage to lead from the front

- Ben Selby, Director, Epigeum (part of Oxford University Press). Ben highlighted the importance of owning decisions and being clear about the importance of integrity when listening, and not practising false democracy

- David Smith, PSC Tech Lead – Consumer Healthcare Separation, GSK who highlighted how important support networks are when listening and emphasised the need to establish good relationships in order to help people feel that they can speak up.

Key:

Key:  Leading the Listening Organisation, which I co-authored with Kevin Ruck and Howard Krais, will be published in early 2024 1. During our research for the book, we found lots of evidence that listening matters but that many organisations only pay lip service to it.

Leading the Listening Organisation, which I co-authored with Kevin Ruck and Howard Krais, will be published in early 2024 1. During our research for the book, we found lots of evidence that listening matters but that many organisations only pay lip service to it.